Design

Design Tenets

-

Copa is intended to accelerate container patching by eliminating waiting on base image dependency chains to update. This is a raison d’etre for the Copa project, so if we figured out a different way to patch containers that still relied on waiting for base images to be rebuilt and republished, we would consider spinning that off into a different project instead of making it part of Copa.

-

Copa is intended to work with the existing ecosystem of container images. The project should have a strong preference for solutions that do not require image producers to create or modify their images in special ways to use Copa.

-

Copa is intended to allow parties other than the image authors to address container vulnerabilities. Copa should require a minimum of special knowledge about the lineage and construction of an image from the user to patch it successfully.

-

Copa is intended to do one thing well and be composable with other tools and processes. Copa does not have to be a universal multitool for container patching. For example, it is preferable that it integrates with popular container scanning tools rather than incorporating custom container scanning into the project itself. Similarly, it does not need to become a general container manipulation tool in the vein of crane.

Design Reasoning

The design of copa arises from the application of those tenets to the observed issues in previous efforts directly update container images via rebasing, for example, the experimental crane rebase:

-

Rebasing requires that all actors involved in creation of the image are coordinated so that some layers can be switched out without breaking the image. Attempting to switch out layers in the container overlay structure is brittle because most existing containers are created by writing over shared configuration files and data stores in base images. For example, an

apt-get installduring image creation will overwrite the dpkgstatusfile in the base image, which will mask any package updates in a rebased layer. Since many existing container scanners rely on the reported package status to find vulnerable package versions, this can cause new vulnerabilities to not be reported or for patched binaries not to be recognized by the scanners.To avoid breaking integration with the existing container ecosystem, copa patches the filesystem bundle as a whole instead of as a collection of layers so that the resulting image state is consistent. This strategy also allows copa to patch vulnerabilties introduced at any layer in the image, including OS packages added in the app layers that is not addressed by a simple rebase. It also supports the core tenet of supporting patching without requiring coordination with all the publishers of the base images that a given image transitively depends on.

-

Rebasing also requires that the user knows a priori what base image (or transitive base image) is in the target image to determine which appropriate rebase image to use. This makes it very difficult for anyone not intimately involved with authoring the image from being able to remediate it, which is one of our tenets.

While it is possible to embed extra metadata or annotations into the target image to facilitate this base image (or transitive base image) lookup, that would require that the images to be patched be modified or created especially to support updates, which goes against another of our tenets to be able to patch images without requiring them to be customized explicitly for that purpose.

The design of copa addresses this by reframing the problem of updating containers and understanding the structure or lineage of a container image to the more specific problem of what packages in a given container image need to be updated. This allows copa to tap into the expertise embedded in the much more robust ecosystem for detecting and remediating vulnerabilities at the package level that already exists today. By making copa an additional remediation step that can be run after a container scan in existing workflows, we avoid both of those issues with an additional benefit: it incurs no additional work on the part of base image publishers to support patching of images based on their base images, the existing channels for publishing update packages is sufficient to service those container images as well.

Architecture

The requirements presented encourage an extensible model in order to support broad applicability. Specifically, there are two areas that the tool will need to accommodate multiple implementations to support more use cases:

- The data schema of various vulnerability scanners producing the input vulnerability report.

- The state management of various package managers and process for applying patches appropriately through them.

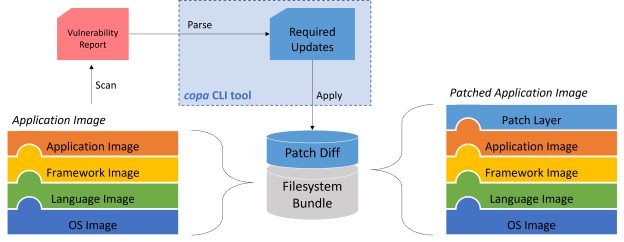

Effectively, copa patch can be considered a command that bridges an extensible Parse action with an extensible Apply action as illustrated in the diagram; the implementation can be thought of as an engine that uses this abstract Go interface to apply security update packages:

type UpdatePackage struct {

Name string

Version string

}

type UpdateManifest struct {

OSType string

OSVersion string

Arch string

Updates []UpdatePackage

}

type ScanReportParser interface {

Parse(reportPath string) (*UpdateManifest, error)

}

type PackageManager interface {

Apply(imagePath string, report *UpdateManifest) error

}

Implementation

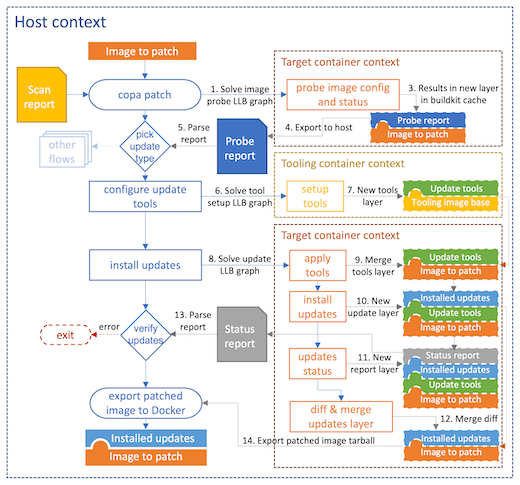

copa is a pseudo-frontend to buildkit implemented as a CLI tool. Effectively, instead of taking a container definition to create from scratch, it takes the reference to the target image to patch and a container scan report and builds a series of LLB graphs for buildkit to execute:

- Actions to probe the image as a filesystem bundle, for example, retrieving the package manager status in the image.

- Within each distribution type identified by the scanner report (e.g. Debian) there can be different ways of applying patches to the target image (e.g. distroless), which can be differentiated through these actions.

- Actions to fetch and deploy tools that can be injected into the target image to perform the patching.

- In cases where the package tools are not available in the target image, a standard version of the OS container matching the target image's is used to stage the necessary tooling for patches.

- In the case of distroless images for example, where there is no valid package status file in the target image, the tooling container is also used to pull down and process the necessary package updates for copy to the target image.

- Although not pictured, this can also be used to obtain tools (e.g. busybox) to be used in the image probing stage as well.

- Actions to deploy the required patch packages to the target image.

copaintegrates with buildkit at the API level because it uses the diff and merge graph operations directly so that it can stage all the necessary tooling in the target image while producing a resulting image that only contains the original image plus a new layer with all the deployed patches.

Tradeoffs

- The core architectural choice of relying on packages as the unit of patching creates a couple of constraints:

- By relying on existing vulnerability scanner behavior that only detects vulnerabilities via presence/absence of vulnerable packages, copa is limited in the kinds of vulnerabilities it can address and false positive/negatives from scanners flow downstream to copa.

- copa depends on individual package manager adapters to correctly deploy patches to the target images, but there is a long tail of compatibility issues that arise depending on the target image itself (e.g. outdated package manager config/keys, invalid/missing package graph, etc.). Overall, the maintenance cost of the project is expected to be non-trivial to address this.

- No support for windows containers given the dependency on buildkit.